A. Narrative

Film uses a minimal narrative:

2 parallel stories of characters pursuing and seeking to achieve their desire.

Their attempts are unsuccessful.

- Ticket Girl attempts to woo the projectionist

- Japanese Boy’s search for sex/love/affection among the gay men cruising for sex in the cinema

- Similarities highlighted through parallel editing/cross-cutting

- Both stories reach their climax around the same time (unfulfilled desire)

- Ticket Girl tries to give the projectionist half of her bun (a gesture that goes unrequited)

Both stories challenge CHC’s representation of desire as unproblematically attained and neatly resolved.

The film wishes to convey how attaining one’s desire in real life is more problematic.

A1. Climax

A1-i. Static climax

The film manages to convey the emotion of the scene while breaking CHC norms.

E.g. Scene of Ticket Girl sitting in the projection room

- Static figure behavior and mise-en-scene

- Smoldering cigarette in the projection room:

- The Projectionist has come by, seen the bun she left for him, but ignored it

- Manages to make static scene of a girl struggling with the pain of rejection engaging

- Doesn’t rely on CHC tropes to convey emotion/narrative beats

A1-ii. Sound and Image Juxtaposition

The film’s “soundtrack” is juxtaposed against the static shot of the Ticket Girl.

- Dragon Inn (a CHC film) continues to play undisrupted, unfeeling or unbothered by the girl’s emotions

- Sense of incongruity

- Tsai challenges CHC: the static girl’s real emotional intensity versus another cliched fight scene

B. Themes

B1. Desire

The film is self-reflexive in making the viewer think about his/her desire when viewing a film.

- CHC film fulfills our (typicall heterosexual) desires as viewers

- Goodbye Dragon Inn deconstructs this, shows scene of homosexual desire instead

- Portrayal of homosexual desire might be unfamiliar to heterosexual audience

- Suggests that your desire is aligned with your sexual orientation

B1-i. Nature of Desire

E.g. Japanese Boy's pursuit of the handsome man

- Offscreen sound of the man’s lingering, disembodied footsteps

- Ghostly, incorporeal quality

- Is the boy pursuing an object of desire that is ghostly, elusive and intangible?

- Nature of the objects of our desire

B1-ii. How Film Influences Desire

Films can influence and shape their viewers’ identities and desires.

E.g.

1. Japanese Boy's desire for the Handsome Man (looks like a movie star)

2. Japanese Boy nudges up to Shih Chun -> gazing at a real movie star

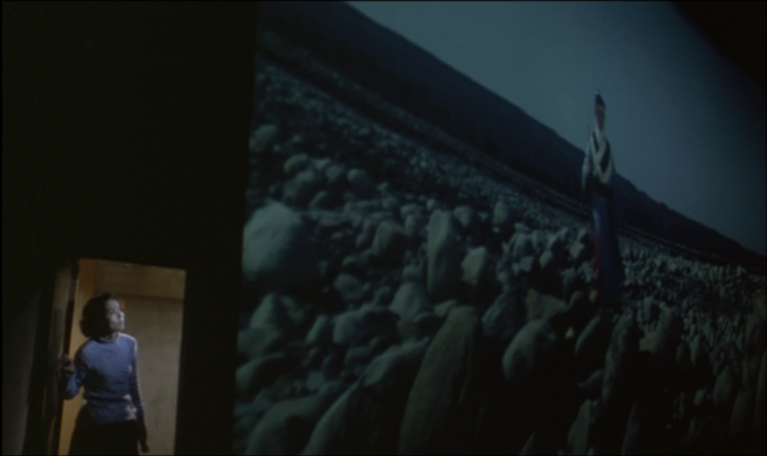

3. Crippled Ticket Girl watching the female swordfighter on screen

- Do the characters desire the screen persona or the actual person?

- Film also influences our conceptions of masculinity and femininity with attractive men and women acting in the film

B2. Title: 不撒 (bu san)

- From the Chinese expression “Bu jian bu san”

Refers to a bond that will not be severed or broken

Contrasts with the idea of saying “goodbye” in the English title

- Means not to depart

- Remain connected, bonded, to linger

- Ties in with the themes of Ghosts

B2-i. Our Bond with Film

- The film depicts the last screening in the grand theater and its closure thereafter.

- How do we remain attached to cinema?

- Essence of cinema is not the physical theater but the inner emotional experience of it

- The film lingers with us and we remain bonded to it

E.g.

Although the Ticket Girl walks away at the end, she remains emotionally connected with the cinema

Shih Chun (old man who plays the Brother Xiao in Dragon Inn) remains emotionally connected to Dragon Inn even after 30 years

Bu San: a tribute to film and a vow to remain attached to it

B3. A Film About Film

Goodbye Dragon Inn invites us to question “What is Cinema?”

B3-i. Sociological Aspect

Cinema as a Social and Cultural Activity

- A social activity engaged in by the masses, by different social groups

- A form of entertainment, i.e. a form of popular culture for the masses

- A form of culture shared across different generations

- A form of culture we are exposed to from childhood (thus leaving a deep impression on us)

Cinema as a Private Experience

Cinema is a “repository”, symbolic for the experiences of different groups

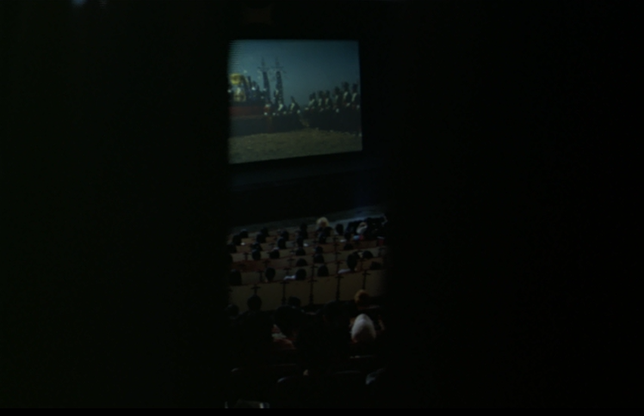

This shot shows that film can be watched as

- A public experience shared with others

- A more secretive, private viewing experience

Specific individuals who have a special relationship with cinema:

- Tsai Ming Liang (he has a cameo)

- Shih Chun

- The Grandfather (he plays the Eunuch in Dragon Inn)

B3-ii. Philosophical Aspect

The film invites us to consider the following ways on reflecting on the nature of cinema.

Concrete World

- Typically conveyed by CHC

- World that is virtually physical and tangible

Semi-concrete World

- Less concrete, less tangible and more evocative

- Intangible experience/memory of a film that lingers in the viewer’s mind

E.g. Not Gotham City itself, rather than your subjective experience of Gotham City - Film is, in the first place, an intangible “light projection”

Pure Illusion

- Artificially created and maintained, nothing in reality

- When you engage with characters on a screen, you actually engage with a pure mechanical illusion

E.g. Shot of the empty theatre

- Exposes the illusion of film

- The true climax of goodbye, dragon inn

- Antithesis to action-packed, climaxes of CHC

- We think that a cinema is a lively place, but in reality, is stark, bare and empty

- Fast-paced nature of the modern world contrasted against the slower, relaxed atmosphere in the theatre

- Out with old, in with the new

The Film’s Stance

Ultimately, the film leans more toward the Semi-concrete World stance.

- Nature falls in the in-between position of being a spectral, ghostly presence

- Neither fully embodied not fully disembodied

E.g. Cinema is literally a flickering light of the projector

Also:

- Dragon Inn exists less as a concrete, visual entity but as an omnipresent aural entity that is intangible, spectral and ghostly in nature

C. Film-making in Goodbye, Dragon Inn

C1. Soundtrack

There is no diegetic sound in the film until the closing scene.

- Non-diegetic sounds easily sway emotions

- Not using non-diegetic sound contributes to realism

- Diegetic sounds gain more depth and significance

The soundtrack of Dragon Inn is omnipresent in Goodbye, Dragon Inn

- Non-diegetic sound in Dragon Inn becomes diegetic sound in Goodbye, Dragon Inn

- Soundtrack used to contrast with the often still images

E.g. Still shot in the projector room - Tsai wishes to challenge CHC but also wants to tribute the film

Sound is used to underscore the nature of cinema.

- Concrete World:

- Underscored by amplified sound in the auditorium

- Semi-concrete World:

- Underscored by ambient sound in the film

E.g. Sounds of the corridor, backrooms etc

- Underscored by ambient sound in the film

- Pure Illusion:

- Underscore by direct sound coming from the film projector

- Mechanical sound

C2. Motifs

C2-i. Ghost motif

Applicable in 2 ways:

- Film is less a concrete entity (as CHC likes us to believe) than an intangible, spectral, hence ghostly entity.

E.g.

- People in the theatre who appear, than disappear -> ghost-like

- Female lady eating chips in the theatre -> film invades reality

- Ghostly nature of the gay men

- Homosexual condition in CHC is ghostly

- Homosexuals as CHC’s ghosts:

- Persons excluded from CHC, thus invisible

- Return in ghostly form to haunt CHC

E.g. Ticket Girl cleaning the bathroom scene

- Door opens and closes on its own

C3. Mise-en-scene

C3-i. Space of the Theatre

- Conventional action replaced with a focus on the theatre’s space

- Empty spaces but also an emphasis on deep spaces (reinforced by deep focus cinematography)

- Characters literally negotiate these deep, complex spaces to pursue their desire

E.g. Japanese boy literally navigates through the maze of narrow corridor spaces in the backrooms.

C3-ii. Props

- Help to convey the narrative of desire

E.g. The bun that the ticket girl offers to the projectionist

- Used to contrast and critique CHC culture of hyped-up images and reality

E.g. Film paraphernalia, movie posters and the cut-outs of movie stars

C4. Cinematography

C4-i. Deep Focus

- Emphasizes the deep space of the theatre

- Theatre as a mysterious, even rich space whose interest rivals the interest of the dramatic action in Dragon Inn

C4-ii. Long Takes

- Long, static takes hinge around small gestures

- Are precondition for and help to generate humor

D. Goodbye, Dragon Inn vs CHC

- Goodbye, Dragon Inn deviates from CHC and shows us that an alternative, non-CHC type of cinema is possible

- Also seeks to criticize CHC for its shortcomings

D1. Deviation from CHC

- Film is not character-centered

E.g. Empty shots without characters

- Characters lack clear, defined traits and goals

E.g. Not immediately obvious what is going on in the Ticket Girl's mind

- No Continuity Editing

D2. Criticism of CHC

D2-i. Reel Life vs Real Life

1. CHC’s tendency to present romanticized, larger-than-life images

- Reality is more sobering

E.g. Skilled female swordfighters in Dragon Inn vs Crippled Ticket Girl in Goodbye, Dragon Inn

2. CHC’s dependence on artificially generated high-drama or high-speed action and events

- Goodbye, Dragon Inn shows us that real life is in fact slow and repetitive

- Film focuses on very ordinary, everyday actions

E.g. eating, drinking, walking, going to the toilet, etc - Seeks to suggest that representing small actions is as equally captivating as Dragon Inn’s hyped-up action

"The movies that we know today are so dominated by storytelling. My question is: is film really only about storytelling? Couldn’t film have other kinds of functions?

…In our own lives there’s no story, each day is filled with repetition…

Film and reality are different, but by removing that kind of artificial dramatic element, I believe that I’m bringing them closer." - Tsai

D2-ii. Critique on Representing Desire

- How CHC does not represent homosexual desire

- How CHC represents the (unproblematic) fulfillment of its characters’ desires.

- Goodbye, Dragon Inn instead portrays:

- The Ticket Girl’s frustrated desire

- The gay men roaming the cinema in search of sex: different pattern of desire

- Goodbye, Dragon Inn instead portrays:

Use of Theatre Space to Represent Desire

- Suggests how desire in real life is more complex

- One needs to negotiate a complex space to attain desire

- Link between desire and space shown by the theatre’s maze-like, complex space

E.g. Long corridors, storage room, projection room, toilets, lobby, ticket counter, etc.

- Theatre is almost it’s own character

D3. Reconciling with CHC

While Goodbye, Dragon Inn critiques CHC, it still pays homage to it.

- Homage payed to Dragon Inn

- In the ending, it retreats to a more ambivalent position

- Shifts to a mode more evocative of CHC

- Uses non-diegetic sound for the first time

E.g. Dramatic rain, elements of nostalgia and romaticization